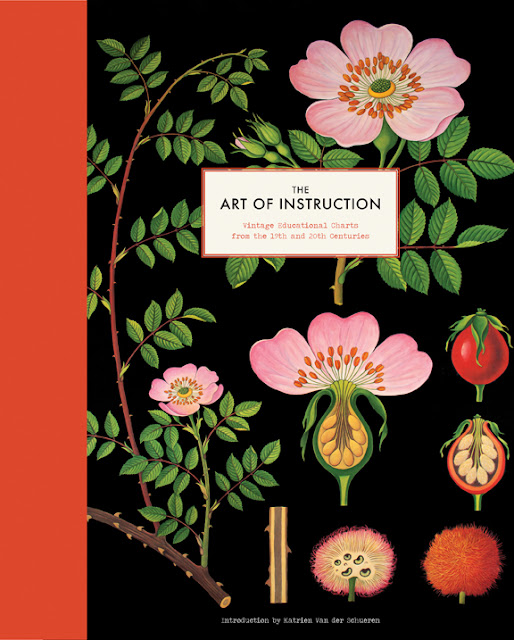

For those excited by the more, ahem, nerdy pursuits (history, botany and zoology, for example), we bring you The Art of Instruction, by Katrien Van der Schueren, owner of the eclectic gallery voila! in Los Angeles, and published this month by Chronicle.

Van der Schueren, who was born in Belgium, has been collecting education charts since she was a child, and it’s a passion she’s turned into a most curious and visually engaging new book. “The first educational wall charts were likely printed in Germany around 1820, when compulsory schooling began to spread throughout Europe and classroom size increased,” she writes in the introduction. “The continent was facing the Industrial Revolution, rapid population growth, and a new perspective on education: learning as a fundamental human right. Governments saw it as their duty to mandate schooling, and this shift created a sustained and thriving market for the illustrated charts.”

The popularity of charts peaked between 1870 and 1920, when they were translated into different languages and distributed around the world. “The size, vibrant color, and rich detail of these illustrated charts not only made them an ideal medium for teaching classifications in nearly all branches of biology, but these characteristics also lent them an aesthetic quality. The charts served a dual role, as both scientific tools and works of art.”

Some of the charts (like the fern seen above) were large in scale and designed so that they could be seen by everyone in the classroom. They needed to be bold in order to capture the students’ interest and were intentionally designed without any or much text. (That was left to the accompanying books.)

“For a century, roughly between 1850 and 1950, charts were fundamental tools in education. The number of charts that had been printed or handmade by individual professors and teachers worldwide during this time was likely in the hundreds of thousands,” Van der Schueren writes. “Today, it’s likely that only a fraction has survived. Smaller class sizes and richly illustrated schoolbooks for individual use gradually diminished the chart’s popularity, as did the introduction of technologically advanced visual aids, such as the slide projector. Although some manufacturers flourished until late in the 1980s, and production does continue today on a small scale, pictorial wall charts gradually lost their universal appeal after the 1960s.”

As we bring you in Entra’s Archivalia column, which highlights newly digitized and previously unseen collections of works on paper, technology has enabled museums and universities to reconsider often overlooked materials in their collections. “Considered ephemeral at the peak of their popularity, these charts were seldom cataloged by the institutions that used them, or even by the companies that printed and sold them,” explains Van der Schueren. The Art of Instruction offers a beautiful reintroduction of the material and, as was the original goal of the charts, makes looking and learning fun.

The book can be purchased through Amazon, or directly through the gallery.

No comments:

Post a Comment